Hong Kong Museum of Art Photo Gallery

Shopping in Canton : China Trade Art in the 18th and 19th Centuries

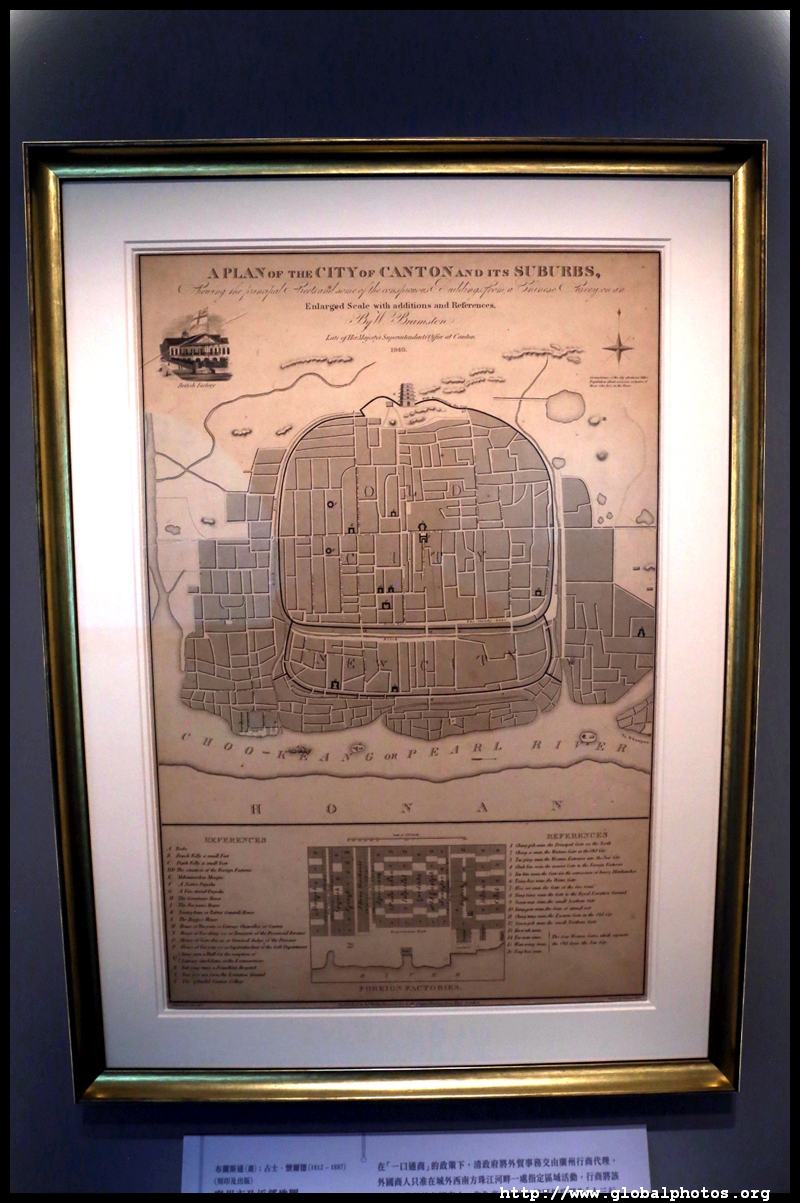

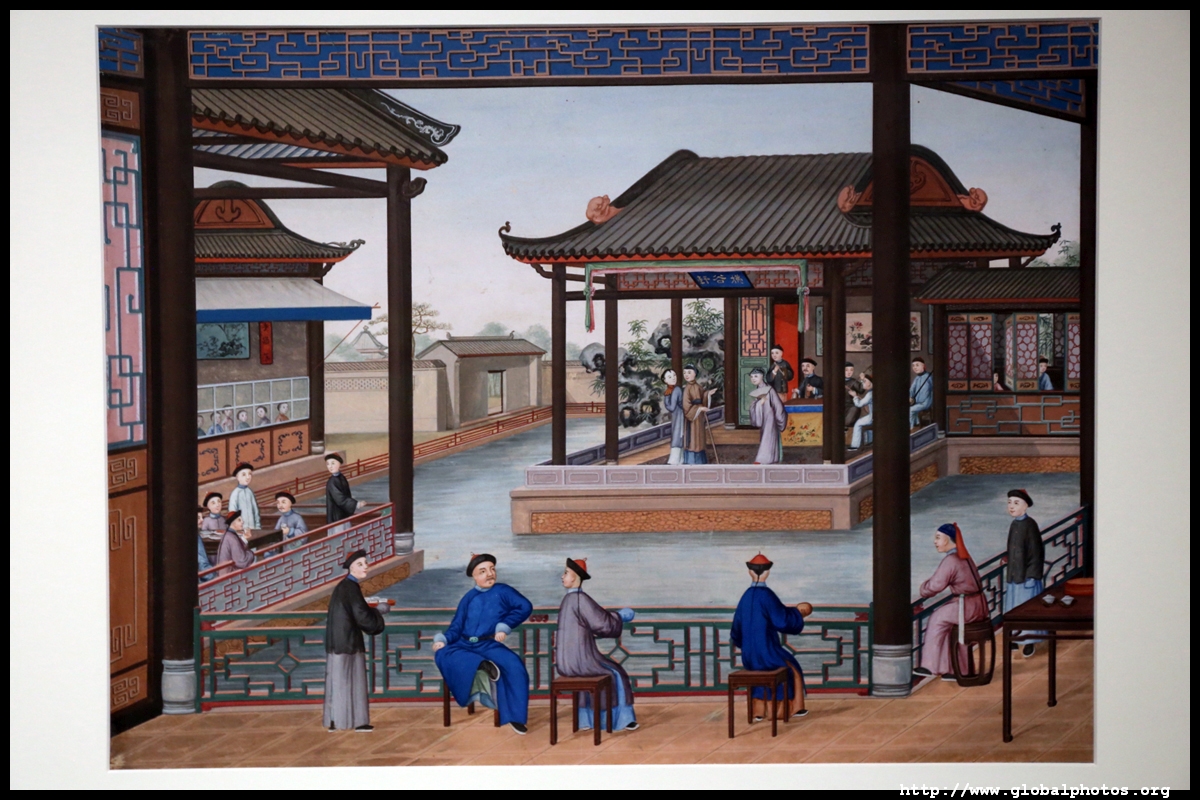

Shopping in Canton : China Trade Art in the 18th and 19th CenturiesThe Qing Dynasty first opened up China's ports for foreign trade in 1685, but centralized trading to Canton in 1757. Until the Opium War, Canton was the only Chinese port for foreign merchants. Foreigners were officially confined to a specific zone in the southwestern suburbs known as the 'Thirteen Factories'.

The 2-3 storey buildings are in Western style and line along the Pearl River. All foreign traders had to stay within these factories and not mingle elsewhere in the city. There was once even a fence here, but a fire in 1822 forced their removal to facilitate evacuation. Offices are on the ground floor while living quarters are above. A large square sits in front of the factories where foreigners are seen talking a walk during their free time, but with the fence gone, it became a bustling centre with hawkers, beggars, gamblers, and more. The fence returned in the 1840s and the foreigners put in private gardens instead.

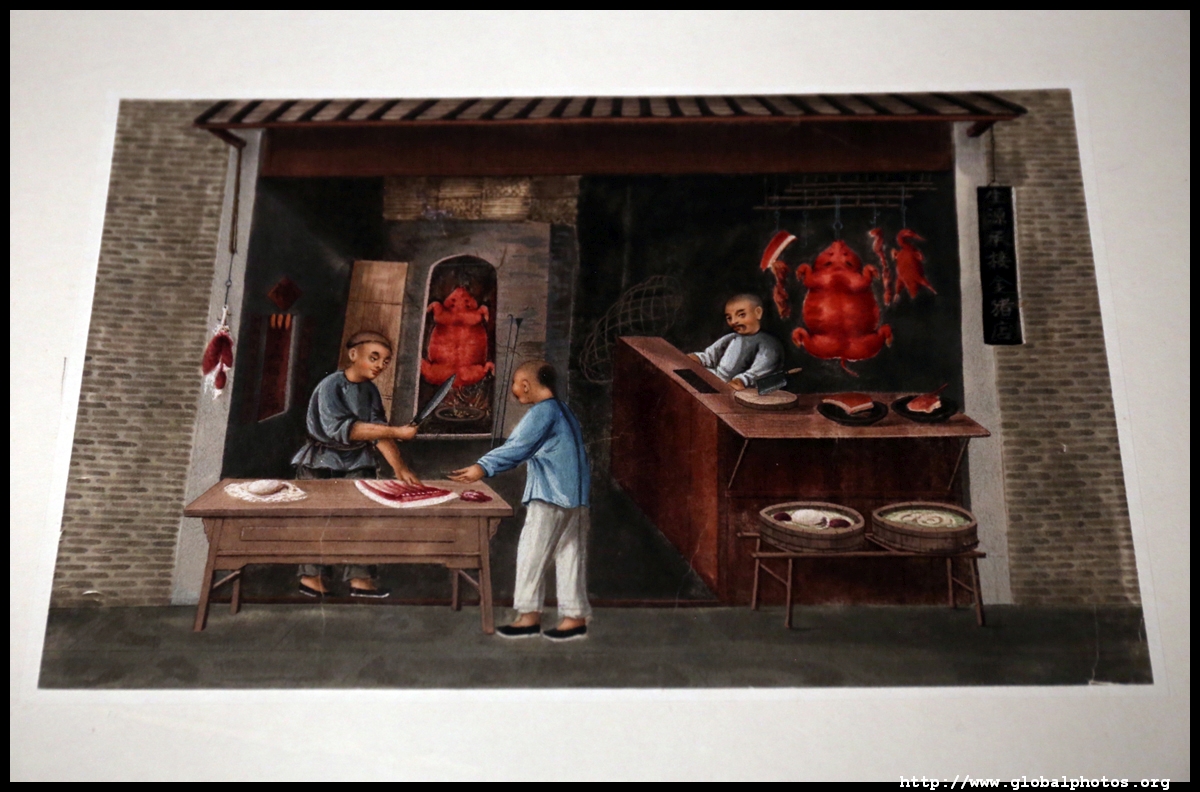

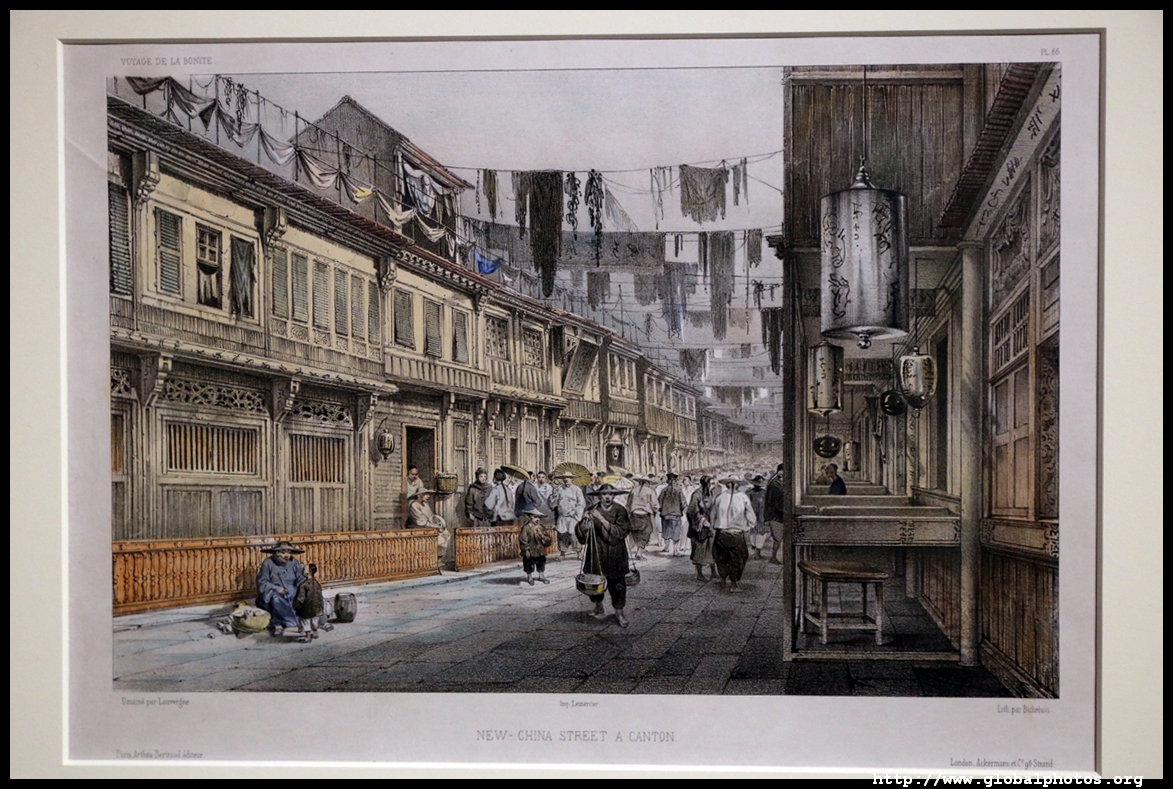

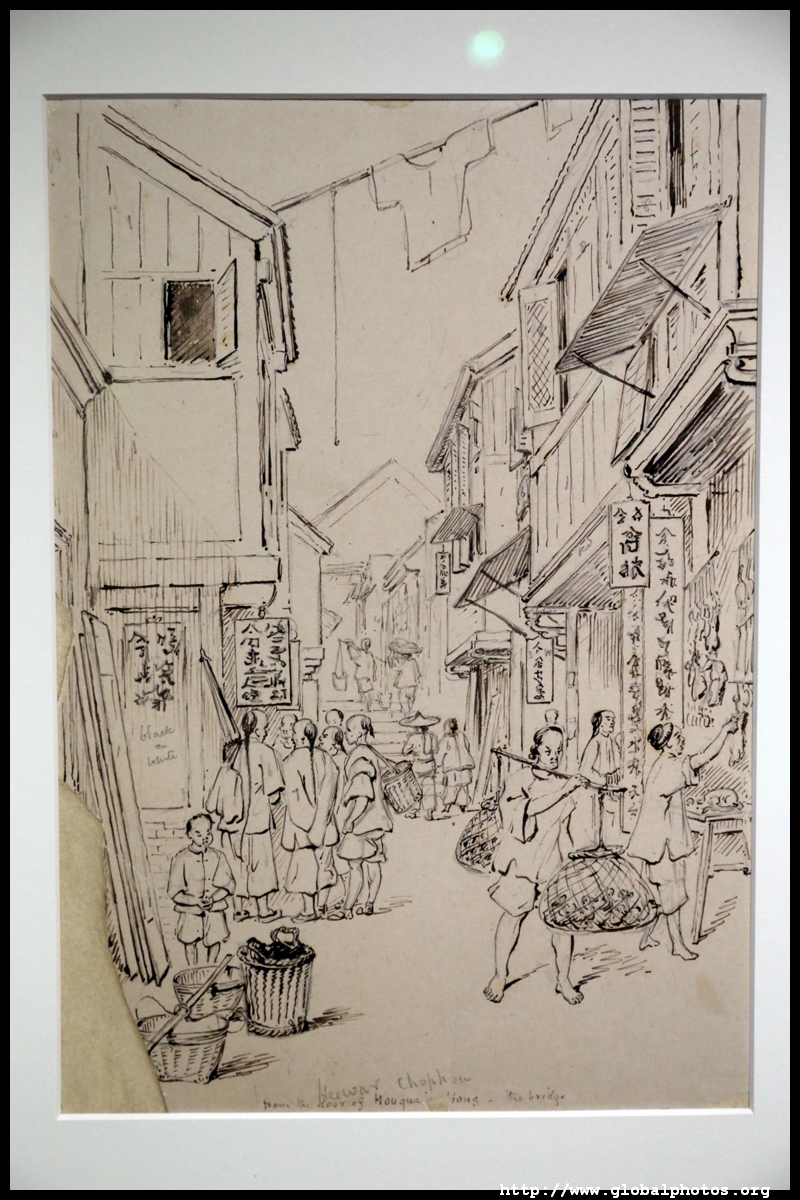

There were 3 main shopping streets near the factories, with small shops lining both sides and gated on both ends. Business owners showcased their wares in their shopfronts with dazzling displays.

Old China Street dates from 1760 where foreign merchants came to buy goods for export, which included porcelain (hence the name), silverware, fans, paintings, and silk.

New China Street was built after the 1822 fire in response to safety concerns. A local merchant donated his family factory between the Danish and Spanish compounds to build this street.

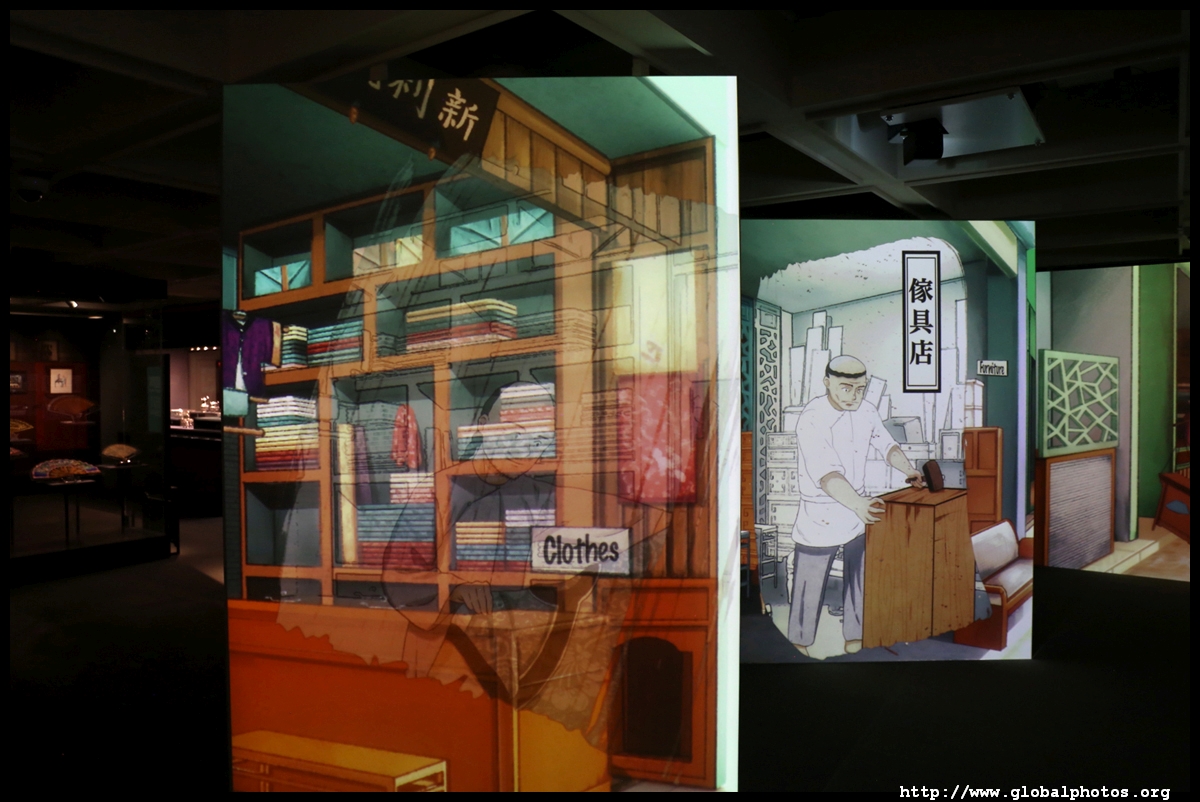

An interactive display showcases the bustling shopping environment in the trade district.

Lacquerware exported from Canton were heavily decorated with intricate patterns. Used to store tea, which was an expensive commodity in Europe, they had to be locked up like safety deposit boxes to protect its contents.

This early 19th century lacquer sewing box catered for Western upper class tastes. The more exquisite the sewing box gets, the more noble the woman owning it feels.

Other lacquer items include a cabinet and even a desk.

Western-style silverware was also a popular export item. While the cost of raw materials wasn't much cheaper in China compared to Europe, the silvermith's wage was far cheaper here.

Fans were a fashion accessory for ladies in the West in the 19th century. Designed specifically for Western tastes, these fans were colourful and had a wide range of materials.

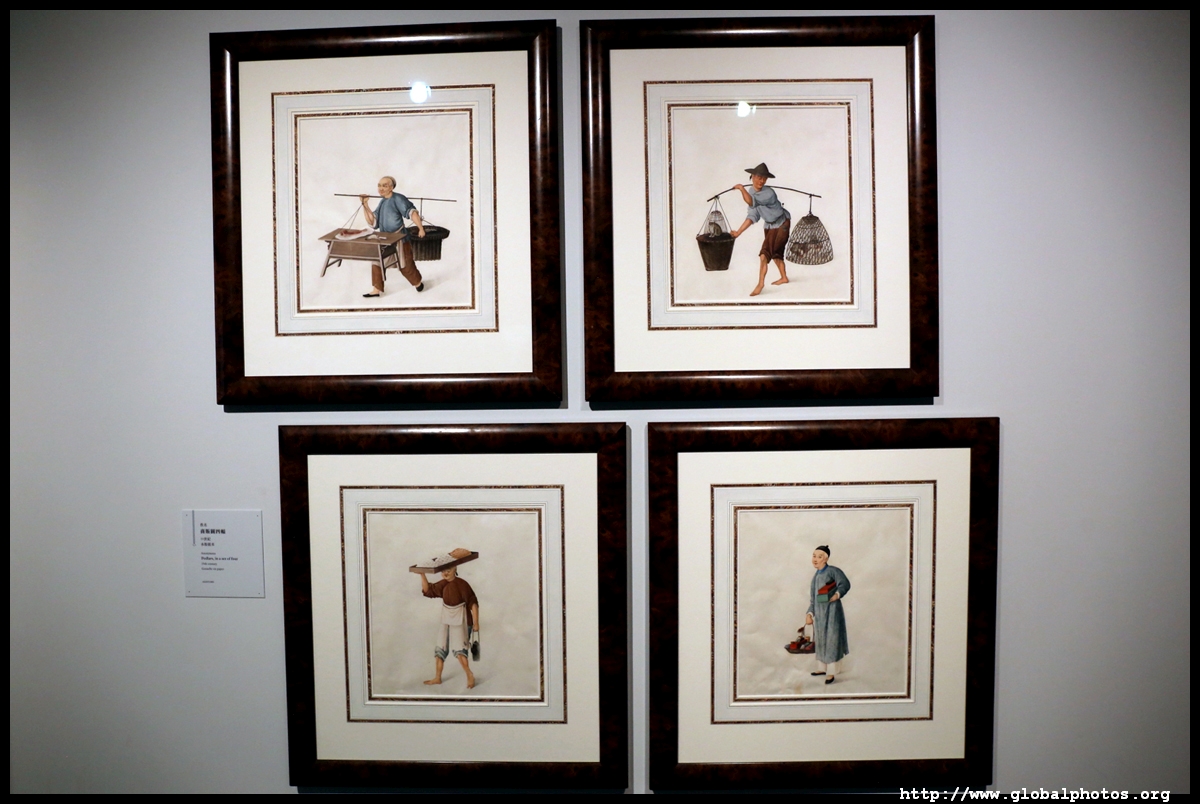

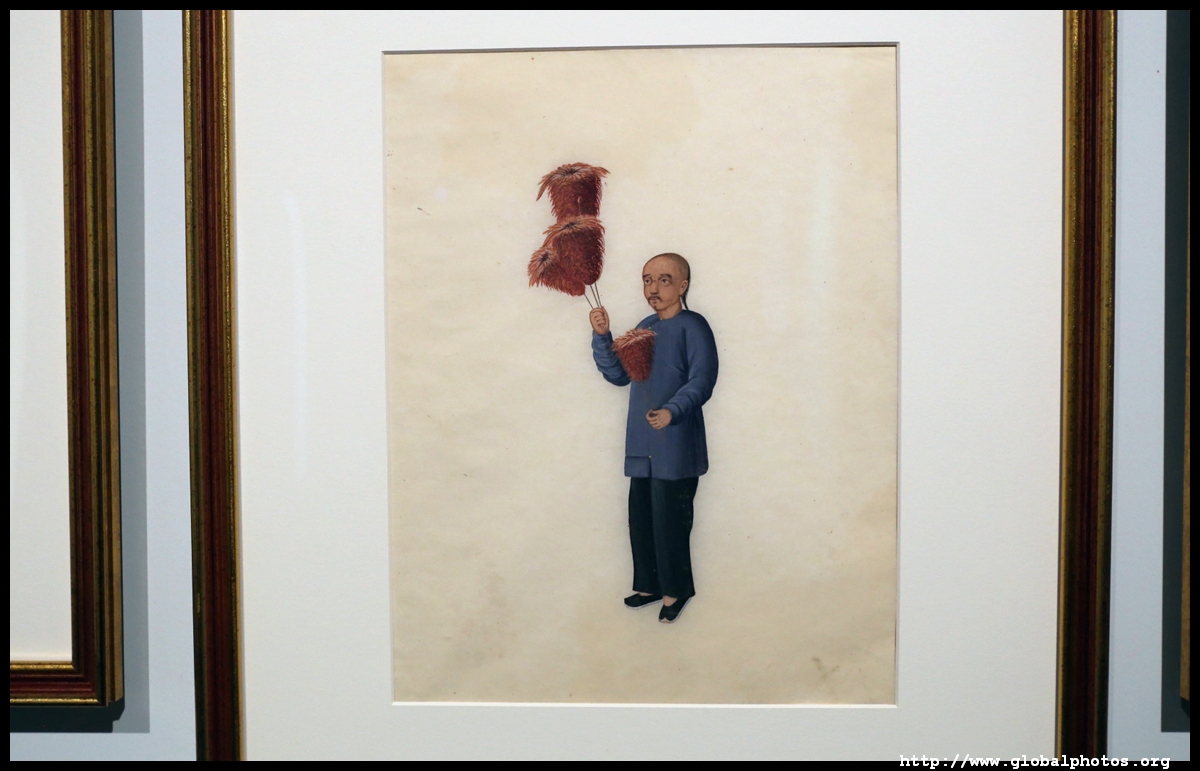

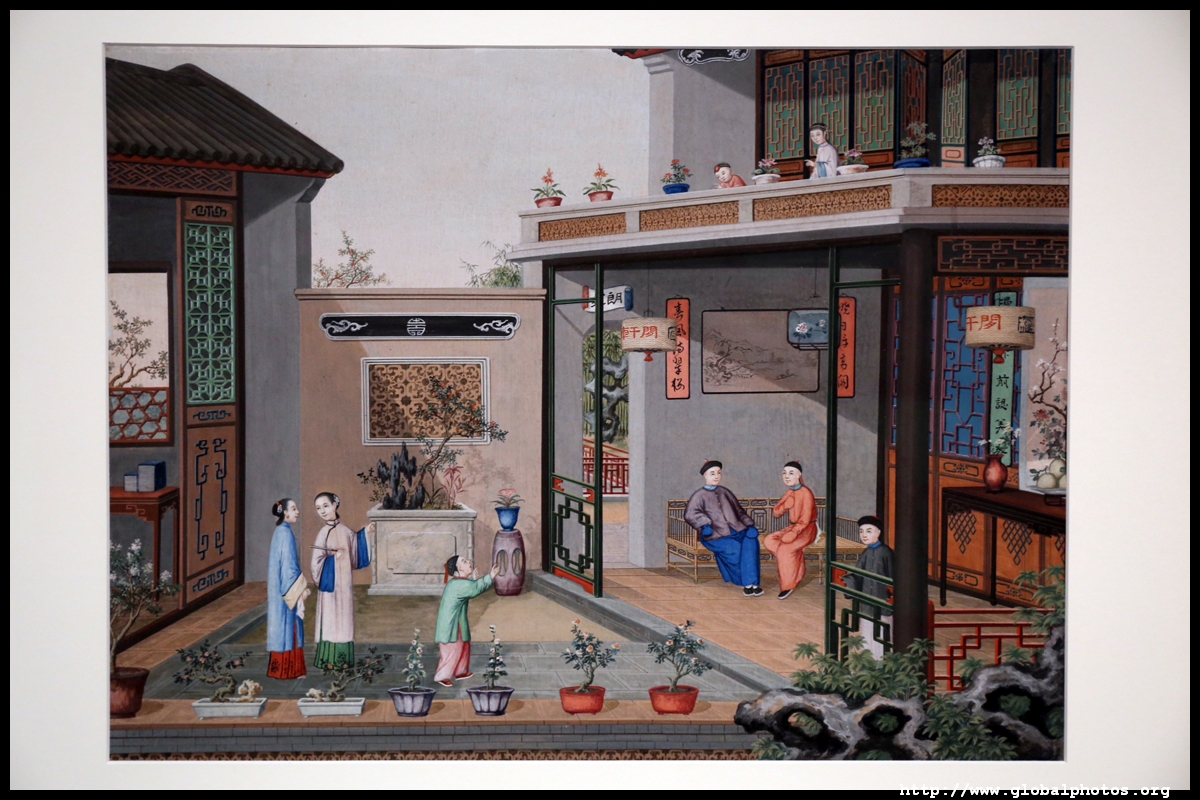

Export painting was a major industry where local artists used Western techniques to produce works that contained both Western and Chinese elements.

Parasols were popular amongst Europe's noble ladies in the 18th and 19th centuries. This Canton export item had traditional styles such as flowers and birds and a carved ivory handle.

Canton is also known for its carvings as the humid climate makes the materials tougher and less likely to break during production.

Chinese export porcelain was termed 'Nanking' ware from the 1760s in Europe, which meant they were premium quality even though they were exported from Canton.

This painted enamel tea caddy reflects the Chinese perception of a Westerner, someone with red, blonde, or brown hair. These works look Western but were made with traditional Chinese painting techniques.

Flower boats such as this one was a disguise for a brothel, and foreigners were banned from boarding.

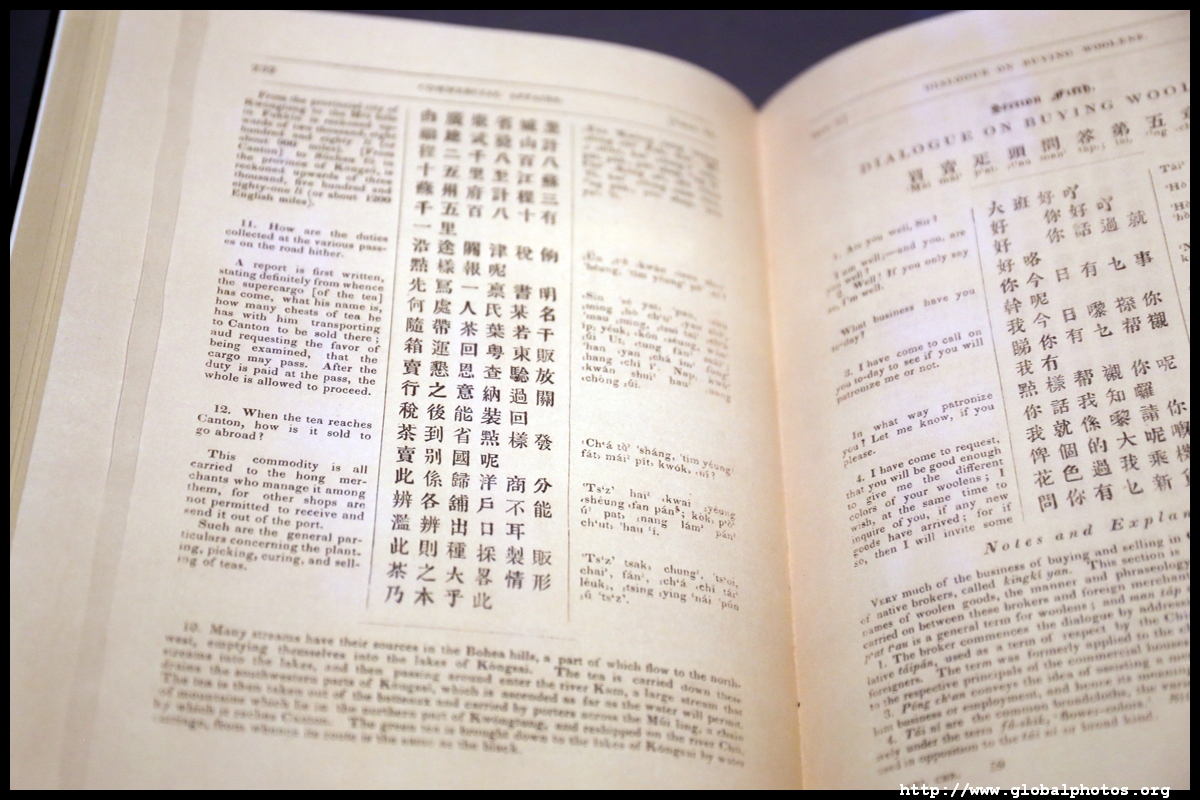

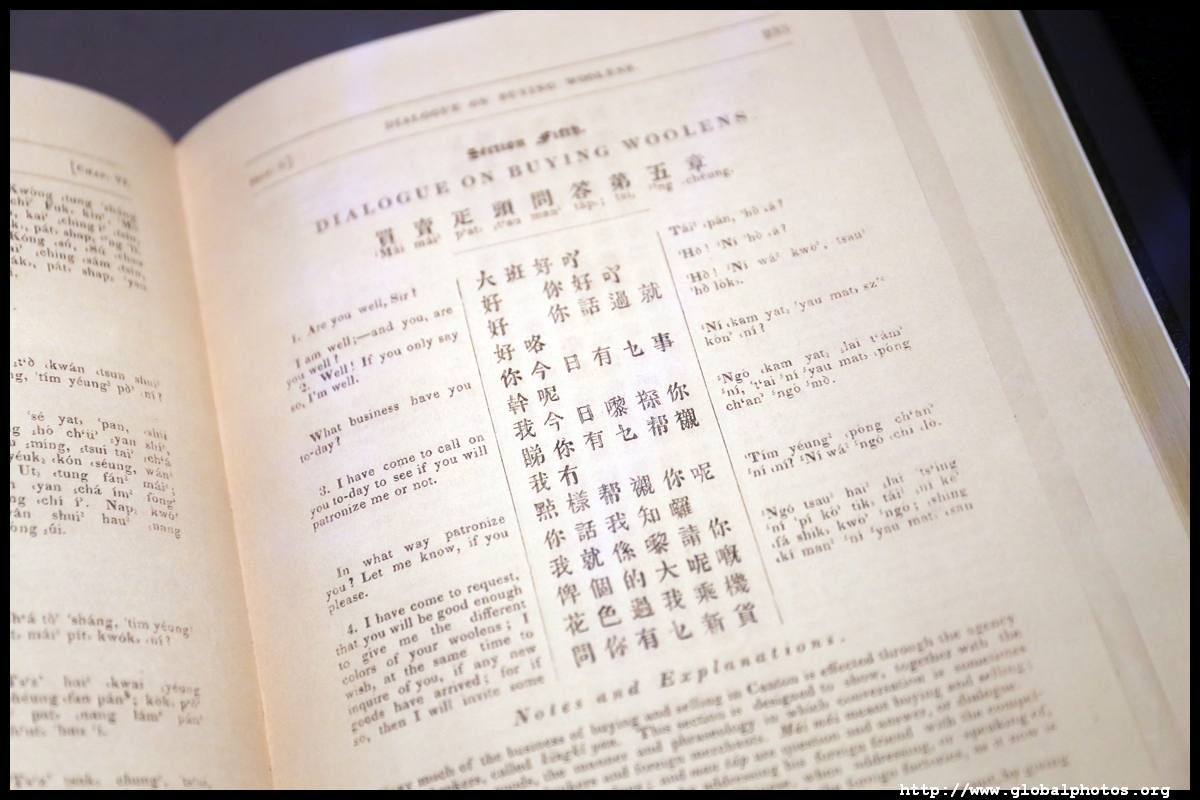

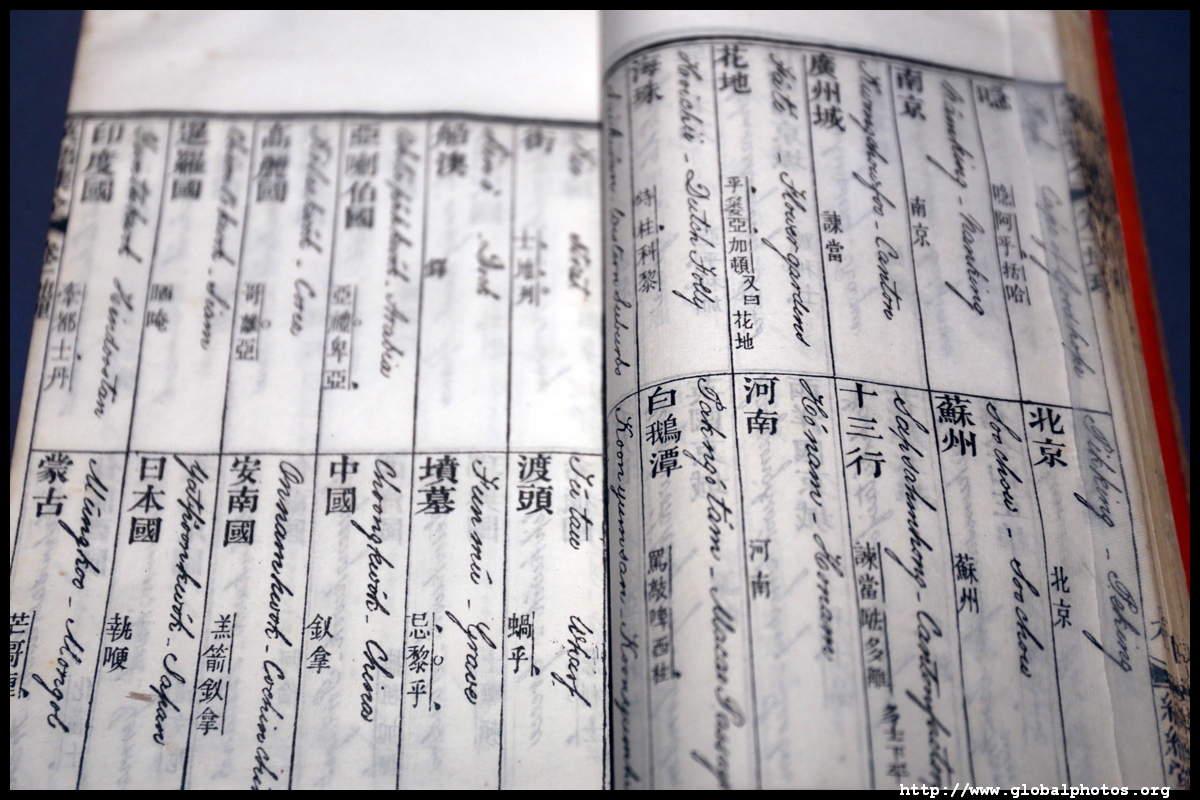

To facilitate communication with the foreign merchants, the Chinese consulted these books that tried to use Cantonese pronounciations to piece together an English phrase.

| |||

Hong Kong Gallery Main Page